GILGAMESH (2021- 2024)

chamber opera for five singers, 11 instruments & electronics (140′)

libretto by Louis Garrick

premiered 28 September, 2024 by Sydney Chamber Opera, Opera Australia, Australian String Quartet & Ensemble Offspring at Carriageworks, Sydney

Conductor: Jack Symonds

Director: Kip Williams

Set Designer: Elizabeth Gadsby

Costume Designer: David Fleischer

Lighting Designer: Amelia Lever-Davidson

Electronics Creation & Sound Designer: Benjamin Carey

Sound Designer: Bob Scott

Gilgamesh: Jeremy Kleeman

Enkidu: Mitchell Riley

Shamhat/ Uta-Napishti/ Scorpion: Jessica O’Donoghue

Ishtar/ Courtier/ Scorpion: Jane Sheldon

Humbaba/ Ur-Shanabi/ Courtier: Daniel Szesiong Todd

Australian String Quartet:

Dale Barltrop, Francesca Hiew: violins

Christopher Cartlidge: viola

Michael Dahlenburg: cello

Ensemble Offspring:

Lamorna Nightingale: flutes

Jason Noble: clarinets

Claire Edwardes: percussion

Jacob Abela: piano

Jasper Ly: oboe/cor anglais

Benjamin Ward: double bass

Melina van Leeuwen: harp

PROGRAM NOTE by Jack Symonds & Louis Garrick

In making an opera after the Epic of Gilgamesh, we follow the example of the Renaissance originators of the operatic art form. We explore an ancient text, uncovering all that speaks to us even thousands of years later, and we couch our reading in the musical and theatrical language of our times.

Like all great epics, that of Gilgamesh (ca. 2100-1200 BCE) is about elemental forces: power, ambition, desire, anger, grief. While the sprawling, fragmentary text defies simple interpretation, what stood out to us in this, the original hero’s journey, was the narrative of a volatile young man who, through the experience of true love and the tragedy of losing it, gains maturity and self-awareness. It’s a relatable and very human story about the transformative power of love.

We have also taken a magnifying glass to Gilgamesh’s relationship with Enkidu. In Andrew George’s authoritative translation, there is talk of Gilgamesh “caressing” his friend and loving him “like a wife.” We found our hero’s apparent homosexuality essential to understanding his emotional journey. And isn’t it fascinating that same-sex attraction is arguably an aspect of the oldest written story humanity has?

At the same time, Gilgamesh is no ordinary person. As the ruler of what is usually considered the world’s first city, Gilgamesh is a symbol of civilisation and some of its worst eventualities: oppression, violence and environmental destruction. His ego-driven mentality leads only to catastrophe and it’s not until the damage is done, both personally and throughout Uruk, that he realises the error of his ways. Like the Epic, our opera ends with a question mark. Has Gilgamesh renounced his odious worldview for ever? Will he rebuild Uruk and be a kinder, more restrained leader? Or is it too little, too late?

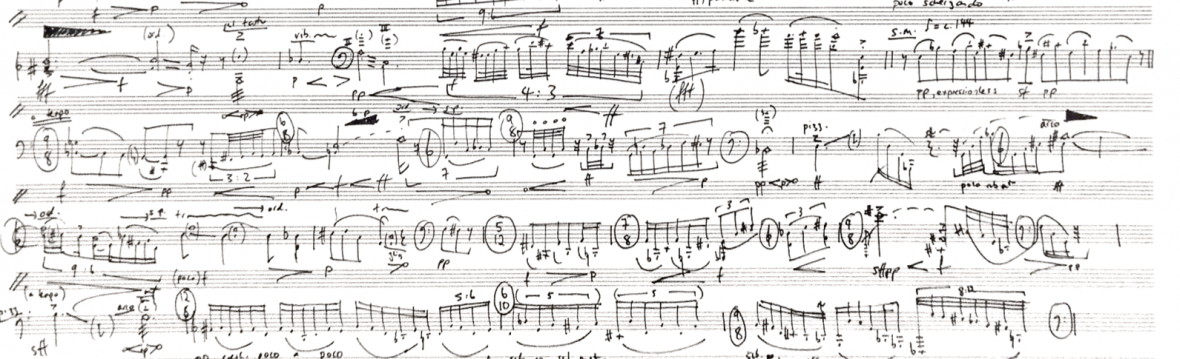

Every role was composed for the singers who premiered this opera, and their musical personalities and expressive proclivities have been encoded with love and admiration into the fabric of the score. Writing for the virtuosic combined forces of Australian String Quartet and Ensemble Offspring has meant that the instrumental lines have gained a complexity and detail quite different from those of an ‘Opera’ orchestra; each scene is focused around specific colours and notes which branch out like an arboreal system to encompass the enormous expressive shifts and character arcs in the Epic.

The Prelude holds the musical ‘potential’ of the whole opera – as Enkidu is created, so too is the world of harmony and timbral associations which will eventually form the mysteries and revelations several hours later. A whole Gilgamesh-specific musical grammar had to be made which could be capable of adapting, continuing, rejecting, renewing or reinventing the practices of almost half a millennium of operatic writing as needed by this extraordinary story.

Balancing the mechanism and history of the genre (love duet, Triumphal Parade, arias of many kinds) with more extended vocalism, instrumental colour and electronic spatialisation is a fundamental part of the opera’s architecture. The addition of live electronics has allowed for a further layer of transformation: from the human to the fantastical/metahuman/eternal and back. Enkidu’s musical journey in particular begins with non-traditional vocal sound, synthesised with instrumental timbre, before being ‘humanised’ into learned singing.

SHOWREEL