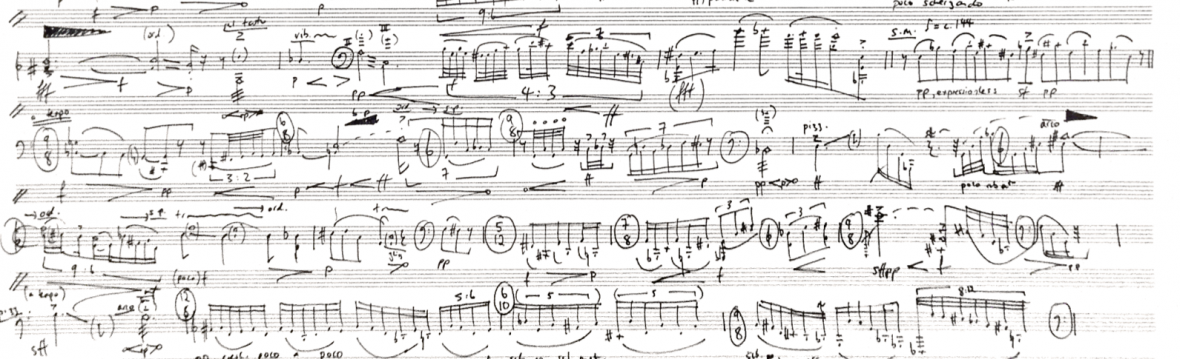

NUNC DIMITTIS (2011)

dramatic scena for baritone, viola and four instruments (28 minutes)

first performances by Sydney Chamber Opera

20- 26th November, 2011 at the Parade Playhouse, NIDA, Sydney

AUDIO EXTRACTS

Aria 1 ‘I’ve had enough’

Dream of an imaginary self-crucifixion

Aria 2 ‘My life is light, waiting for the death wind’

Mitchell Riley- baritone, James Wannan- viola. Sydney Chamber Opera Orchestra conducted by Huw Belling

PROGRAM NOTE

The words Nunc dimittis are the Latin name of a canticle from a text in the second chapter of Luke named after its first words, meaning ‘Now dismiss…’ In thinking of a work to pair with and ‘continue’ Bach’s “Ich habe genug” (1727), I thought that it could be dramatically potent to set the same text as Bach, coming to very different musical and expressive conclusions. All of Bach’s text is used, and there are several lines from T.S. Eliot’s “A Canticle for Simeon” spliced in. Eliot’s 1928 poem- coming almost exactly two hundred years after Bach- is a deeply ambiguous, personal refraction of the Christian text of the actual ‘Nunc dimittis’, which itself is the direct source material for the (anonymous) poetry of “Ich habe genug”.

Knowing Nunc dimittis was to be performed after Ich habe genug, it was important for me to attempt to capture the spiritual ambit of Bach and take it on a new course without altogether negating it. It would have been easy indeed to be some sort of ‘anti-Bach’ and write a sarcastic, damning parody of it, but I personally don’t find this very interesting. What is much harder, and much more rewarding, is finding a musical language that allows various expressive and some technical aspects of Bach to appear transformed, not negated, by the cultural experience of the intervening centuries.

More and more, I see the three arias of the Bach as three very different ways of looking at the problem of the interface between life and death in the presence of religion. I don’t find that Bach’s ending is in any way a resolution of the text’s difficulties, which makes it even more tantalising. The furious dance alternating religious ecstasy and terror is really quite ambivalent in the most powerful sense, and it is from there that I wanted to find some way of ‘releasing’ all of the conflicting modes of thought in the Bach into a piece which can absorb their disparity and function with what unities they do possess.

The form of the piece divides Bach’s and Eliot’s texts into two large arias with obbligato viola (in contrast two Bach’s three arias separated by recitatives) around a central ‘Dream’ for the baritone and string quartet meditating on the words ‘I’ve had enough’. In the first aria, the precipice of death is reached in an unsteady acceleration towards the terrifying, then potentially consoling, idea of eternal sleep. The contrasts are violent, the rhetoric caught in a constant tension between uncertainty, acceptance and resignation. After the ‘dream’, the second Aria is unreal, half-lit and mysterious, attempting to find common points of language and even resolution of all the musical and textual difficulties of the first Aria in single long lines. I imagine here a state of consciousness beyond the very ‘human’ passions of the first Aria, which hopes to create, as if in a waking dream, a realisation of the death-of -life and the living- in -death.

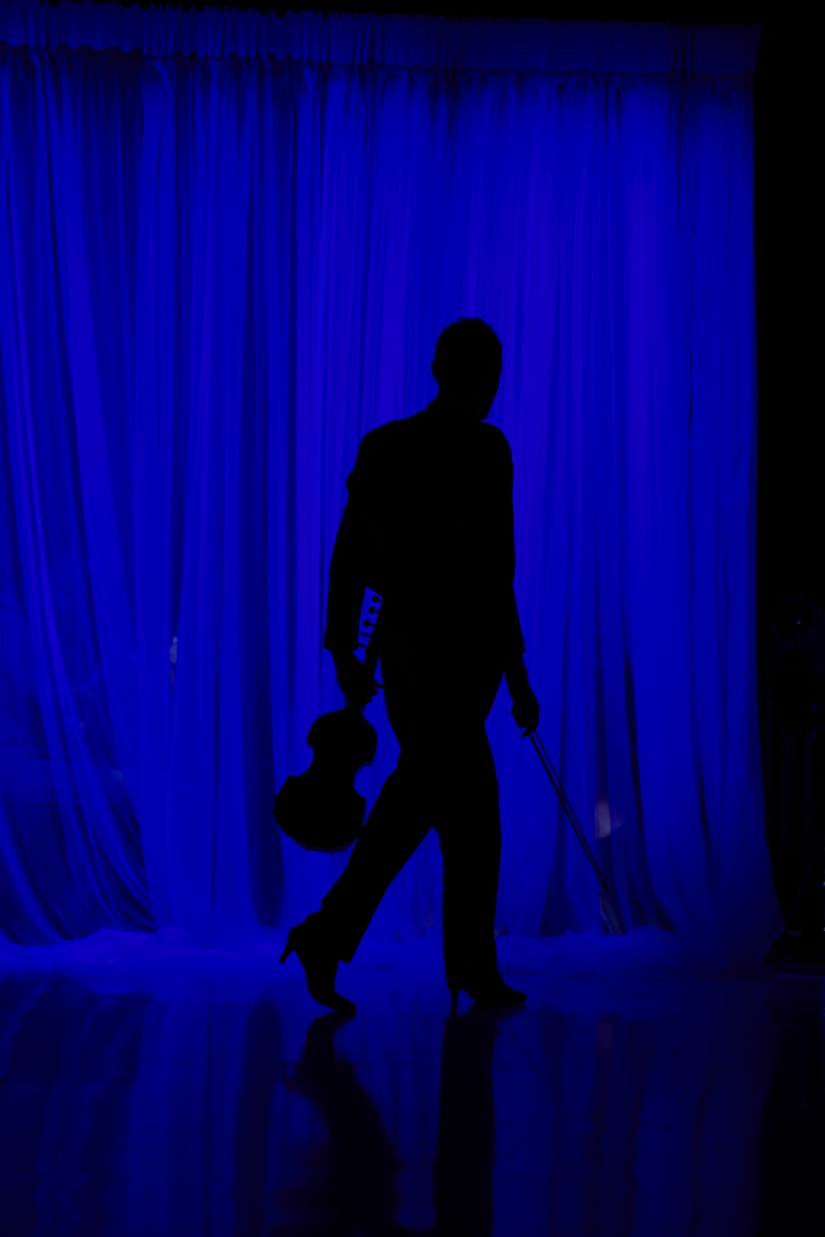

VIDEO EXTRACTS

(trailer)

(showreel)

Photography: Zan Wimberley

Photography: Zan Wimberley